This most excellent article comes from Austin Kleon's blog:

Saturday, May 12th, 2007

I came to David Hockney’s Secret Knowledge, like many other beautiful books, by way of Edward Tufte. It’s a fantastic book with the basic thesis that from the early 1400′s on, painters and artists were employing the aid of optics (mirrors, glasses, lenses) to achieve a new stunning realism. If you want a great introduction/summary of the findings in the book, Lawrence Weschler’s article, “Through the Looking-Glass: Further adventures in opticality with David Hockney,” is available for free in full-text with color photos from The Believer online.

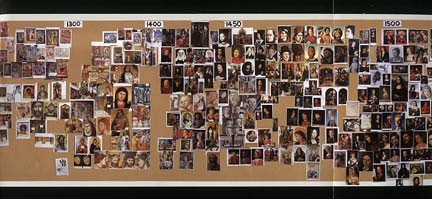

While I enjoy the mind-blowing content of his argument, what I enjoy most is Hockney’s way of looking. He came about his thesis by comparing color photocopies of 400 years of paintings and drawings side-by-side in a gigantic graphic collage timeline:

[Hockney] cleared the long two-story high wall of his hillside studio (the studio retains the general dimensions of the one-time tennis court over which it was built), installed a photocopier in the middle of the space, and, drawing on his brimming private horde of art books and monographs, effectively proceeded to photocopy the entire history of European art, shingling the images one atop the next–1300 to one side, 1750 to the far other, Northern Europe on top, Southern Europe below–a vast, teeming pageant of evolving imagery (and in some ways Hockney’s most ambitious photocollage yet).

It was from this gigantic collage that he was able to pinpoint a period at which painting seemed to change — somewhere around 1430, painting obtained an “optical” look.

Hockney argued that that look dominated European painting for centuries–just how far back he wasn’t yet sure–and that it only lost its hold on Western artists with the invention of the chemical process, in 1839, after which painters, now despairing of matching the chemical photograph for optical accuracy, finally fell away: awkwardness returned to Western painting for the first time as generation after generation of artists –impressionists, expressionists, cubists and so forth–endeavored to convey all the nuances of lived reality (time, emotion, multiple vantages, etc.) that a mere photograph couldn’t capture.

The wall, or art history from 1400-1900 becomes a three-part story: you have pre-optics (awkwardness), optics (the disappearance of awkwardness), and post-optics (the return of awkwardness).

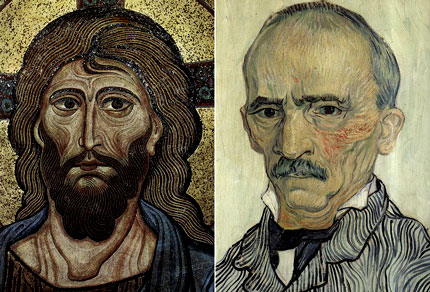

“Awkwardness,” Hockney was saying, wheeling around, “the disappearance of awkwardness, the invention of chemical photography, and the return of awkwardness. The preoptical,” he wheeled once more, “the age of the optical, and then the post-optical, which is to say the modern. And look here.” He led me over to the corner where the two ends of the procession abutted. On the one wall he’d posited, as endpoint, Van Gogh’s portrait of Trabuc (1889); next to it, on the other, was a Byzantine mosaic icon of Christ from about 1150.

These two images together just blow my mind. It just makes so much sense. Here we are in a world where everything can be captured in perfect detail from a camera, and it takes the human hand to render it in some kind of form that actually seems closer to our experience. We don’t see life from one fixed-focus lens. We see it from two eyeballs, two ears, etc. And this is why, I think, we still love the human awkwardness of cartoons, or abstracted drawings: it can produce an experience that a photograph can’t.

Anyways, there’s a ton of other great stuff in Hockney’s book and Weschler’s article. Highly recommended.

No comments:

Post a Comment