CLR INTERVIEW: Jeff Warren is a producer for CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) radio. In his new book, The Head Trip, he writes about his personal exploration of the various states of human consciousness. Below is his interview with the California Literary Review.

- The Head Trip: Adventures on the Wheel of Consciousness

What do you mean by the term “Wheel of Consciousness” in the title of your book?

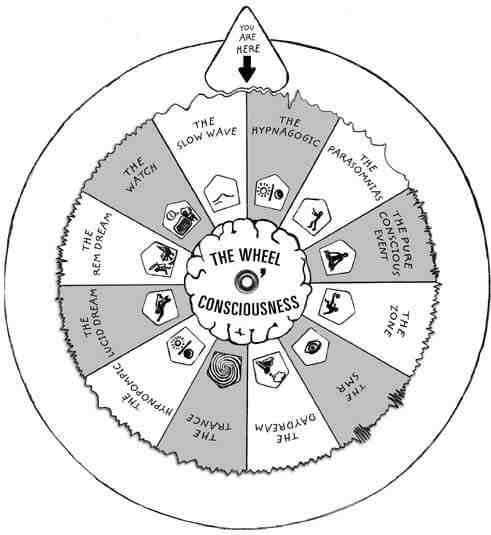

The Wheel of Consciousness is my metaphor for some of the dramatic and dramatically strange ways our awareness changes through sleeping, dreaming and waking. Picture a wheel in the centre, folded, involuted. Around it is a jagged halo that represents the brain’s electrical activity. The wheel is the brain, it pushes up from below, changing the contour of consciousness from one moment to the next. The wheel is spun, in part, by our biological clocks, which move us through changing levels of alertness during the day and the various stages of sleep at night. It is a hardware model, and one of the things I discover on my adventures is this model is incomplete: the brain—at least the reductive modular view of the brain—is not enough. Because pushing down in the other direction is the mind itself, a still-mysterious top-down catalyst for all kinds of unusual special effects within awareness.

The thesis of my book is that consciousness is far more variegated and expansive that most of us realize. Waking, sleeping and dreaming are like three points of a huge triangular table, on whose surface we careen like billiard balls. Often these balls move automatically, little Newtonian machines in a cause-and-effect trance. But we’re capable of changing our course at any time, capable, in fact, of levitating right off the table and zinging into a much larger and stranger room. There is nothing religious about this – these things are available for anyone to experience, and neurobiology is beginning to provide a loose sort of explanatory framework.

The Head Trip is about what happens when you investigate consciousness from experience forward, instead of—in the style of the vast majority of consciousness books—theory back. My experiences—my adventures—take me all over the world, from lucid dreaming workshops to meditation retreats, neurofeedback clinics, sleep laboratories, hypnotist chairs and more. I eventually realize that each of the twelve states of consciousness I profile has its own specialized brand of knowledge and insight. They have personal as well as scientific value, which should hardly be surprising, though it was for me, perhaps because, like so many of us, I have a tendency to think and act and live on automatic.

The “Wheel of Consciousness”

Are certain states of consciousness more “real” or “authentic” than others?

This is one of those simultaneously complex and simple questions that can be answered in one gnomic line (if you’re a mystic), one efficient paragraph (if you’re a scientist) or a rambling ten-volume treatise (if you’re a philosopher), to the dissatisfaction of everyone.

From the point of view of the subject, all experience is real, insofar as it is has a felt, experienced quality. Where it gets fascinating is the waking / dreaming distinction. When we fall asleep sensory input is removed and we move through a world simulation constructed from memory and experience. We call this The Dream. It feels perfectly real, has a vivid fully immersive quality that most of us don’t question—that is, unless we’re able to wake ourselves up inside the dream and conduct a proper lucid investigation. But that’s another matter.

In waking we tend to think The Dream vanishes, evaporates in daylight like morning dew on grass. But it doesn’t. The unsettling Matrix-esque truth here is that we all live in world-simulations, pretty much all of the time. The brain isn’t out in the world; it’s locked in a dark box in your head. Patterns of information ting against our senses and get routed into the brain for model assembly. One of the core insights of the science of perception is our models of the world are heavily interpreted—our own expectations and cultural mores and personal history shape “The Real,” so that in some ways our personal little submarines move through an ocean of our own making. This is The Dream, subtle but always there, seeping into our interiors, influencing the waking world in ways we are only beginning to appreciate.

One state of consciousness you describe in your book is called “The Watch.” What is it?

All of us wake up in the night, though these wake ups are usually so short we forget they ever happen. But sometimes they’re longer, in fact there is intriguing scientific and historical evidence which suggests that pre-Industrial Revolution the great majority of humankind may once have slept in a bi-modal sleep pattern, that is, we slept once in early evening, and then again in the early morning. In between we rose to a peculiar state of consciousness called the Watch. In the Watch high levels of prolactin circulate in the brain, thought by one scientist to contribute to a kind of meditative calm. If the state is celebrated and not simply endured it can be luxurious: we skip along the surface of sleep, bobbing back and forth between waking and dreaming, our waking thought informed my dreaming images, and our dream ideation shaped by waking concerns. It’s as if we are looking inside but also out, each state mixing into the other in all kinds of novel and wonderful ways.

You mention that its absence may explain the insignificance of mythology in our lives.

Yes, in the sense that dreams are a great oceanic source of mythology and fantasy. Imagine how it may once have been. Warm in our beds we wake from The Dream. The darkness provides a screen onto which we can project lingering images and scenarios. In this protected mid-night eddy, where few daytime concerns intrude, we turn the details of our dream over and over in our minds. We make new connections, we steep in emotional atmospheres. We slip back and forth between worlds. Dreams are the original teaching stories. But in 21st century life most people discount them. It’s a shame; like myths, they have much to tell us. Plus who couldn’t use a little more lounging in bed?

The chapter on lucid dreaming was fascinating. What is a lucid dream and how have scientists verified its existence?

When we think about our dreams they often have a washed-out, etiolated quality. But this is not what dreams are like—this is what our memories of dreams are like. Dreams when we’re actually in them are vivid and thrillingly real. The best vantage from which to see this is from the lucid dream, when we “wake up” inside a dream and recognize the manufactured nature of our dream surroundings. Ordinarily in dreams we race around like headless chickens, running from perceived threats, pleading with 10-ton bowls of porridge or whatever. The point is we don’t think very carefully about the larger – often absurd – context. In lucid dreaming we are better witnesses. Various waking capacities – self-consciousness, rationality, memory, agency – are back online, and we can wander through the dream interrogating dream characters, conducting experiments, whatever. Most people fly around looking for opportunities to have sex. I usually strike out in that regard, in fact my dream characters almost universally ignore me. Perhaps this is because I am disappointingly uncoordinated in my lucid dreams; I walk like a drunk, crashing into hedges and buildings, and when I try to fly I seize up like a voodoo doll, flip onto my back, and summersault helplessly while all around dream forces hum with oblique intent. Thus I have democratized the state for losers everywhere.

Still, the fun house quality of the mind at night is only part of its appeal; lucid dreaming also has scientific value. It is an unparalleled opportunity to examine some of the operating rules of consciousness—after all, there is no sensory input to overwhelm the normal mechanisms of attention. The sensory tide has receded; all kinds of psychological crustaceans lie revealed on the exposed stretch of beach, to use an admittedly weird and probably inappropriate metaphor. One of the things I most enjoyed about writing The Head Trip was trying to identify the psychological “laws” which govern the dream world, universal operating rules roughly equivalent to the laws of physics in waking.

The story of how sleep scientists verified lucid dreaming’s existence is fascinating and a little too involved to get into here. It involves moving eyeballs and crackling EEG machines and can be read about on dozens of dodgy websites. In fact lucid dreaming and altered states in general are paragons of internet knowledge. My book is a distillation of all that ephemera, filtered through the sensibilities of reliable investigators.

What is a “Pure Consciousness Event?”

Earlier I referred to waking, sleeping and dreaming as forming three corners of a huge triangle within which all non-drug induced alterations of consciousness take place. In fact, this is not quite right. In Indian philosophy there is reference to a “fourth state.” This is Pure Consciousness, a term coined by the Transcendental Meditators but one that applies to a common experience found in practically every meditative tradition and regularly visited by initiates.

It is a deeply mysterious state, more mysterious even than slow wave sleep. Science has very little to say on the matter, though it is beginning to take reports of Pure Consciousness seriously. Essentially a Pure Conscious Event is what happens when all the content of consciousness—all the thoughts and sensory input and emotions and whatever else – when all that recedes and you are left with an empty luminous void. To extend the beach metaphor I used above, first the sensory input waters recede, but then the beach itself recedes, it’s like a great mystical existential tide that sucks back all psychological matter so that the observing “I” is left floating in space. In fact even the observing “I” is gone, even space. It’s paradoxical and profound and of no help whatsoever if you’re trying to order a pizza.

Is it a realistic goal for us to direct our own states of consciousness?

Yes it is. The brain’s plasticity is thrilling. You can learn new mental habits and burn them into your cortex, you can reroute old neural grooves. Most of us fire down our neural luges like Jamaican bobsledders. We hug the track, we imagine (if we imagine at all) that our course is predetermined. But with a little practice you can fly right over the lip and set out on a new path. Fuck the judges! Meditation teaches you this, so does neurofeedback, and hypnosis and lucid dreaming. These are all techniques for self-regulation, tools for changing our experience of waking, dreaming and sleeping in ways that are profoundly hopeful and useful and cool and fun.

Of course you may drive yourself insane trying to get there, but that’s why we have teachers, and books—books like mine, to draw a road map and indicate the sharp turns and the many swamps and farmer’s fields into which one may crash one’s car, as I crashed mine, where in fact, my car is right now, idling but on its last drops of petrol, driver’s hands on the heat vent, eyes on the gathering darkness. Time to ditch the car and set out on foot; some of the best trips begin at night.

(Note: car crashes and roadmaps should not be confused with bobsled and luges, two different through perilously similar metaphors)

No comments:

Post a Comment