Map reveals the activity of genes across the entire brain to help shed light on neurological and psychiatric conditions

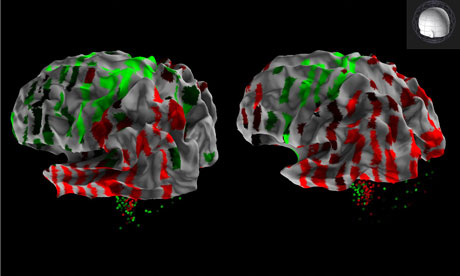

3D rendering from the Allen Human Brain Atlas showing the expression a single gene across the cortex of two human brains, revealing areas with higher (red) and lower (green) expression. Photograph: Allen Institute for Brain Science

A comprehensive atlas of the adult human brain that reveals the activity of genes across the entire organ has been created by scientists.

The map was created from genetic analyses of about 900 specific parts of two "clinically unremarkable" brains donated by a 24-year-old and 39-year-old man, and half a brain from a third man.

Researchers at the Allen Institute for Brain Science in Seattle said the atlas will serve as a baseline against which they and others can compare the genetic activity of diseased brains, and so shed light on factors that underlie neurological and psychiatric conditions.

"The human brain is the most complex structure known to mankind and one of the greatest challenges in modern biology is to understand how it is built and organised," said Seth Grant, a professor of molecular neuroscience at Edinburgh University who worked on the map.

"This allows us for the first time to overlay the human genome on to the human brain. It gives us essentially the Rosetta stone for understanding the link between the genome and the brain, and gives us a path forward to decoding how genetic disorders impact and produce brain disease," he said.

The power of the brain arises from its neural wiring, its variety of cells and structures, and ultimately where and when different genes are switched on and off throughout the three-pound lump of flesh.

From more than 100 million measurements on brain pieces, with some only a few cubic millimetres, the scientists found that 84% of all genes are turned on in some part of the organ. Gene activity in next door regions of the cortex, the large wrinkly surface of the brain, was very similar, but distinct from that in lower parts, such as the brain stem.

More detailed analysis of the cortex revealed patterns in gene activity that corresponded to regions with specific roles in the brain, such as movement and sensory functions.

The atlas revealed no major divide in gene activity on the left and right sides of the brain, suggesting that expertise generally handled by one hemisphere, such as language, comes from more subtle differences than the study could spot.

Though both brains came from men of a similar age and ethnicity, the pattern of gene activity was so similar that researchers suspect there may be a common blueprint for the expression of genes in the human brain. Work is now under way on donated tissues from both sexes to check how consistent that genetic blueprint might be among people with healthy brains.

Scientists have constructed similar genetic atlases for rodents in the past, but the shortage of donated human brains, coupled with the destructive nature of the tests, and the 1,000-fold increase in size, meant a human equivalent was more of a challenge.

Writing in the journal Nature, the scientists describe how they first scanned the donated brains and then chopped them into tiny pieces. For each lump, they measured activity levels for all of the 20,000 or so genes in the human genome.

The atlas, which overlays the genetic results on to a 3-D image of the brain, is freely available for researchers to use online.

Grant said that future studies will look to connect the genetic brain atlas with other genetic studies or brain scans of abnormal or diseased brains. That could highlight genes that play a role in brain conditions and point the way to drug treatments that dampen down or ramp up gene activity.

Clyde Francks at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in the Netherlands is already using genetic data from the Allen Institute for Brain Science to pinpoint genes that give rise to brain asymmetries in a set of 1,300 Dutch students.

No comments:

Post a Comment