From yee Wiki:

Totem poles are monumental sculptures carved from large trees, mostly Western Red Cedar, by cultures of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. The word totem is derived from the Algonquian (most likely Ojibwe) word odoodem [oˈtuːtɛm], "his kinship group".

Totem poles are typically carved from the trunks of Thuja plicata trees (popularly called "giant cedar" or "western red cedar"), which decay eventually in the rainforest environment of the Northwest Coast. Thus, few examples of poles carved before 1900 exist. Noteworthy examples include those at the Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria and the Museum of Anthropology at UBC in Vancouver, dating as far back as 1880. While 18th-century accounts of European explorers along the coast indicate that poles existed prior to 1800, they were smaller and fewer in number than in subsequent decades.

The Maritime Fur Trade gave rise to a tremendous accumulation of wealth among the coastal peoples, and much of this wealth was spent and distributed in lavish potlatches frequently associated with the construction and erection of totem poles. Poles were commissioned by many wealthy leaders to represent their social status and the importance of their families and clans. By the 19th century, certain Christian missionaries reviled the totem pole as an object of heathen worship; they urged converts to cease production and destroy existing poles.

Totem poles were never objects of worship. Very early European explorers thought they were worshipped, but later explorers such as Jean-François de La Pérouse noted that totem poles were never treated reverently; they seemed only occasionally to generate allusions or illustrate stories, and were usually left to rot in place when people abandoned a village. The association with "idol worship" was an idea from local Christian missionaries of the 19th century, who considered their association with Shamanism as an occult practice.

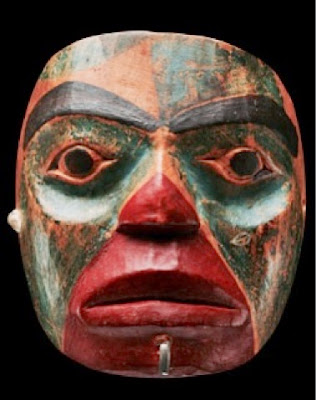

The meanings of the designs on totem poles are as varied as the cultures that make them. Totem poles may recount familiar legends, clan lineages, or notable events. Some poles celebrate cultural beliefs while others are mostly artistic. Certain types of totem poles are part of mortuary structures, and incorporate grave boxes with carved supporting poles, or recessed backs for grave boxes. Poles illustrate stories that commemorate historic persons, represent shamanic powers, or provide objects of public ridicule.

"Some of the figures on the poles constitute symbolic reminders of quarrels, murders, debts, and other unpleasant occurrences about which the Native Americans prefer to remain silent... The most widely known tales, like those of the exploits of Raven and of Kats who married the bear woman, are familiar to almost every native of the area. Carvings which symbolize these tales are sufficiently conventionalized to be readily recognizable even by persons whose lineage did not recount them as their own legendary history." (Reed 2003).