Art. Comics. Icons from the Age of Anxiety. Jazz. Psychology. Crime Fiction. Finance. Blues. Science. Surf. Satire. OCD.

Wednesday, December 17, 2014

In the Blogs: The Real Connection Between Ambition And Mental Health

Monday, December 15, 2014

Saturday, December 13, 2014

In the Blogs: The Downside Of Treating Mental Illness Like A Physical Problem

Tuesday, December 9, 2014

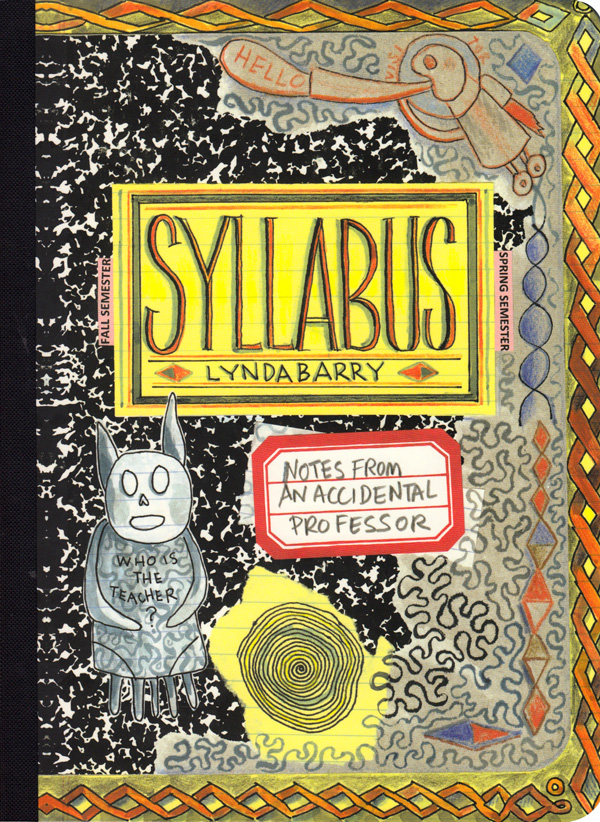

From the BrainPickings newsletter: Lynda Barry’s Syllabus: An Illustrated Field Guide to Keeping a Visual Diary and Cultivating the Capacity for Creative Observation

How to master the infinitely rewarding art of “being present and seeing what’s there.”

“It gives me such a sense of peace to draw; more than prayer, walks, anything,” Sylvia Plath wrote in her diary when she first began working on her little-known drawings. “The great benefit of drawing … is that when you look at something, you see it for the first time,” the great Milton Glaser observed in sharing his wisdom on life. “And you can spend your life without ever seeing anything.”

“It gives me such a sense of peace to draw; more than prayer, walks, anything,” Sylvia Plath wrote in her diary when she first began working on her little-known drawings. “The great benefit of drawing … is that when you look at something, you see it for the first time,” the great Milton Glaser observed in sharing his wisdom on life. “And you can spend your life without ever seeing anything.”

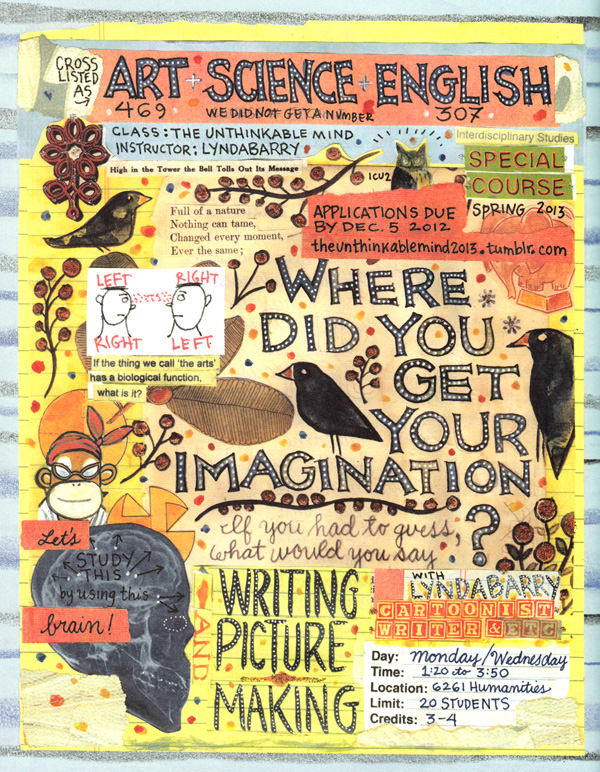

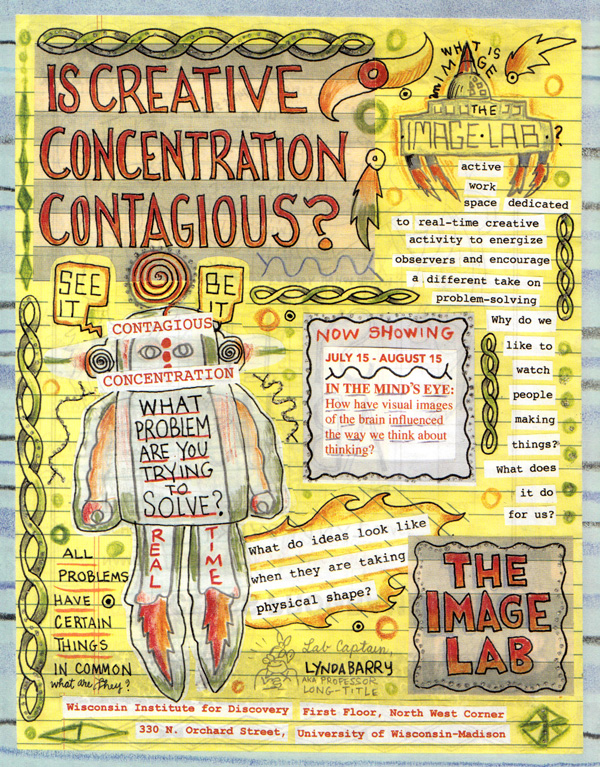

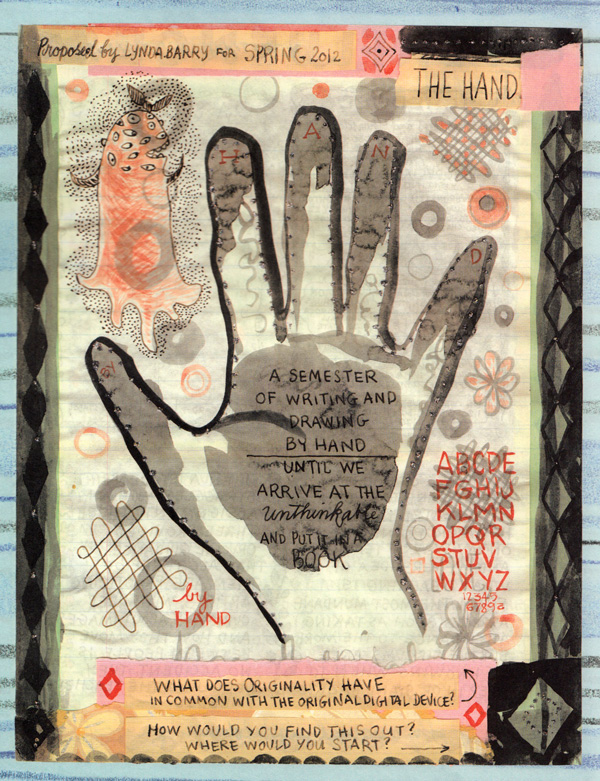

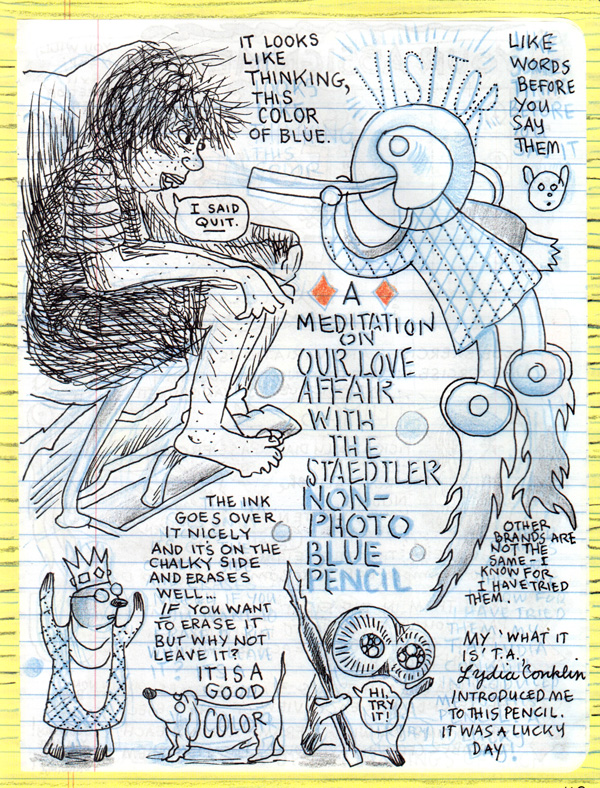

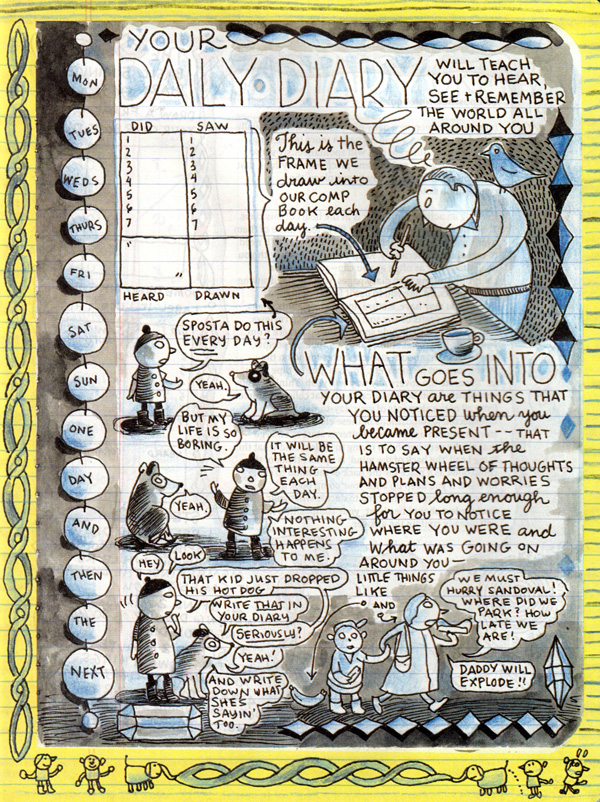

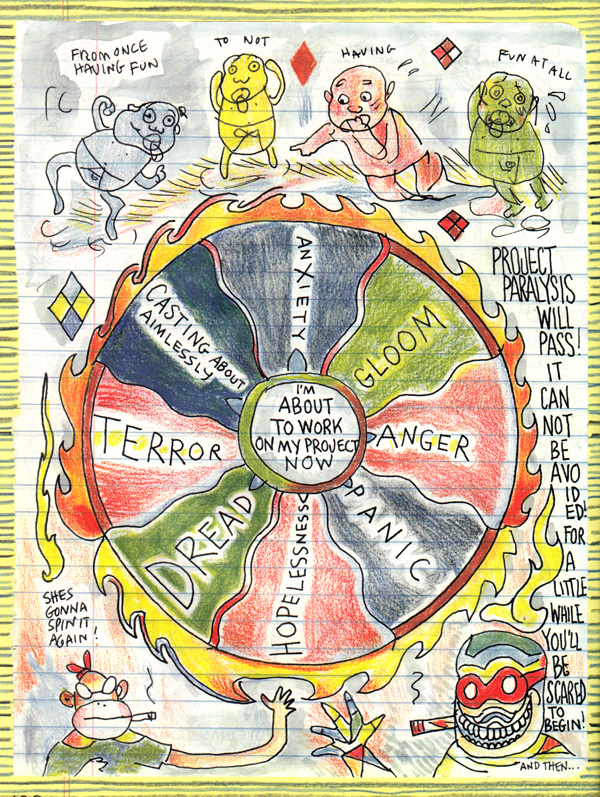

Hardly anyone has explored this delicate relationship between drawing and looking, drawing and experiencing, drawing and thinking with more rigor, wit, and insight than Lynda Barry, one of the greatest visual artists of our time. In 2011, Barry joined the faculty at the University of Wisconsin to teach a class titled “The Unthinkable Mind” — a wonderfully unusual interdisciplinary course exploring the biological function of the arts and the psychological mechanisms of the creative impulse by blending cognitive science, visual art, and writing. Barry’s magnificently illustrated syllabus notes and class assignments, many of which she had released on her Tumblr throughout each semester, are now collected inSyllabus: Notes from an Accidental Professor (public library | IndieBound) — a slim but infinitely invigorating compendium of illustrated exercises, instructions, and meditations on everything from how to keep a diary (because, as we know, the creative benefits of doing so are vast) to memorizing things effectively to navigating the psychological phases of the creative process to why art exists in the first place.

Echoing Joan Didion’s unforgettable reflections on keeping a notebook, Barry traces her own journey and what is to be gained by those endeavoring to master this simple, powerful practice:

I began keeping a notebook in a serious way when I met my teacher Marilyn Frasca in 1975 at the Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington.

She showed me ways of using these simple things — our hands, a pen, and some paper — as both a navigation and expedition device, one that could reliably carry me into my past, deeper into my present, or farther into a place I have come to call “the image world” — a place we all know, even if we don’t notice this knowing until someone reminds us of its ever-present existence.

I wasn’t quite 20 years old when I started my first notebook. I had no idea that nearly 40 years later, I would not only still be using it as the most reliable route to the thing I’ve come to call my work, but I’d also be showing others how to use it too, as a place to practice a physical activity — in this case writing and drawing by hand — with a certain state of mind.

This practice can result in … a wonderful side effect: a visual or written image we can call “a work of art”; although a work of art is not what I’m after when I’m practicing this activity.

What am I after? I’m after what Marilyn Frasca called “being present and seeing what’s there.”

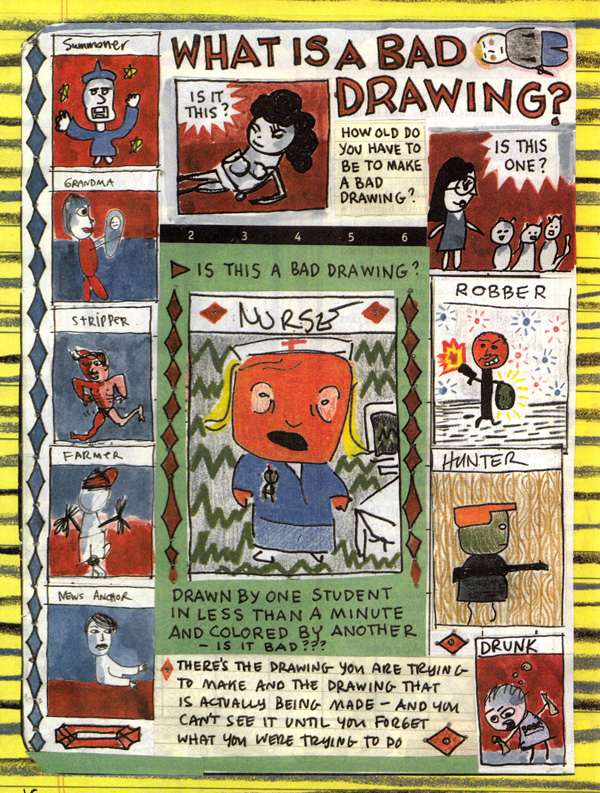

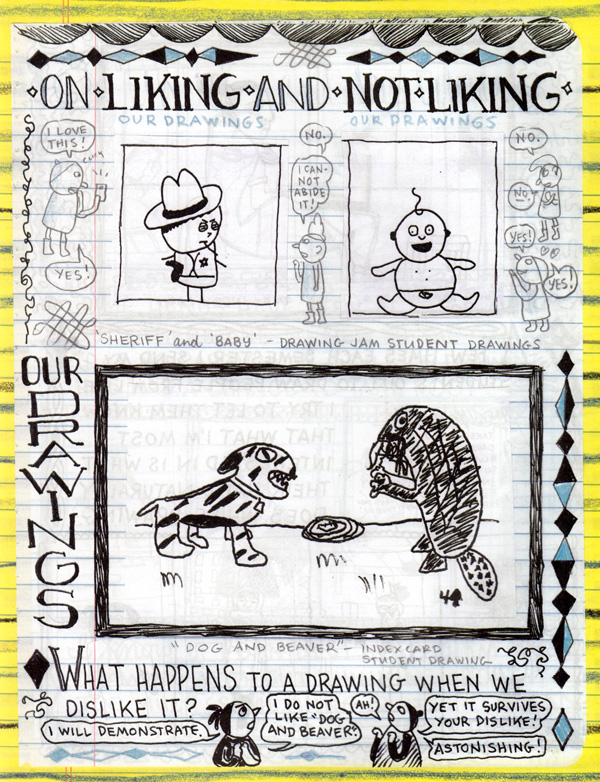

While Barry’s exercises are decidedly and refreshingly practical, they don’t shy away from the philosophical — she explores subjects like the eternal question of what makes good art and how drawing can change our already elastic perception of time. Along the way, she illuminates these questions by assigning readings as diverse as Emily Dickinson’s poetry and Iain McGilchrist’s The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World.

All in all, Barry’s Syllabus makes not only tangible but also practically attainable the deep intuition that some of history’s greatest minds have articulated — the idea that keeping a notebook or a diary, whether visual or otherwise, is one of the most consciousness-expanding ways of bearing witness to our experience and our journey through this world.